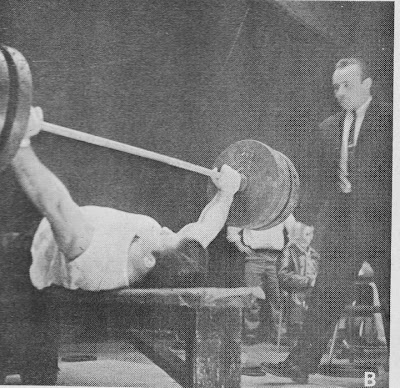

Pete George, victorious at the 1955 World Championships.

Click Pics to ENLARGE

The Psychology of Weightlifting, Part Two

by Pete George (1961)

Mental Preparation for the Contest

Whether your aim is a district, national, world you have only one day in the year to win your goal. It makes not one bit of difference how good you are the day before or the day after. Obviously if you are at all serious about competition you must plan to be at your peak on the big day. In this article we will discuss what you can do to condition yourself mentally to do your best when it counts the most.

You must start planning for your next contest as soon as your last one is over. This is the time to decide how much you will want to do. Your contest goal must be determined on the basis of a number of things including your long-range goal, your recent rate of progress, the results of your last contest, and your expected competition. You must consider all of these points so you can convince yourself that your aim is realistic. Some men say aim high and you will end up high. This is good strategy only if you can truly make yourself believe you can do it. To shoot for a goal that you would like to reach but don’t really think you can will only frustrate you and cause you to lose confidence in your ability.

Once you have selected the poundages you intend to do, write them down so you may check on them from time to time. Then mentally do these lifts as you will on the day of the contest. You should visualize the bar loaded to the correct weight. Then see yourself going through every detail of the successful lift to the point where the referee signals down and your spirit is elevated up. Do this once or twice a day. But let me warn you, you will probably not find this mental lifting easy. It takes patience and practice but the rewards are well worth it.

Before a big championship I usually took two days rest. If the contest fell on a Sunday I would try to arrange training sessions on Tuesday and Thursday. Most of the men on the United States team followed a similar schedule. My Tuesday workout would be a fairly heavy one. That is, I would work up on each lift as high as I could go on singles without missing an attempt. Then I would drop down and do a few moderately heavy reps. I always felt it very important not to practice failures during this last week. Bob Hoffman would constantly tell us, “You must accustom your muscles to success.” This is especially good advice near a contest for both your form and your mental attitude.

During my Thursday session I would only work up to my intended starting poundages in the contest. I would never attempt more even if the last weight felt very light. It is always better to go out of your final workout feeling that you could have done more rather than to risk failing on a heavy weight. This also helps protect you from injuries at this late date.

Speaking of injuries, never enter a contest with an alibi. Don’t make a public announcement that you have a sore back, have had a cold, were to busy to train, or could not sleep last night. An advance excuse reduces your desire to win. I don’t mean to say that these conditions could not happen to you. If you feel that by competing you may cause yourself harm, than withdraw from the contest, of check with a doctor or your coach who will keep your condition a secret. Once you have definitely decided to enter tell anyone who asks that you are in top shape. Excuses will not help you, but they will give your competitors a boost in morale. After I decided to follow this policy I was amazed to find the way many of my aches and pains left me.

As you approach the contest it is normal for the tension to mount. This is not particularly harmful unless it upsets your stomach or robs you of sleep. On the last day or two do not discuss lifting during meals. Before going to bed try to make yourself busy with something interesting enough to keep your mind off the competition. Many athletes like to go to a movie the night before a contest. Also keep yourself occupied the next morning – there is no value in speeding up your adrenalin at this point. Try to forget about the weights until you start your warmup.

How much weight should you use for your warmup? I never used more than 135 even when I would start with over 350 on the clean & jerk. I would spend enough time with this poundage to make certain that all my muscles were warm and flexible, but would not take a heavier weight until I was on the platform. This was because of my reaction to competition and the spectators. Weights would always feel lighter on the platform than in the warmup room. Attempting a heavy weight backstage would tend to discourage me. This is not true with all lifters. There are some who do as well in the gym as they do in the contest. I would suggest that these men warm up to within 10 pounds of their starting weight. This would greatly increase the confidence of such lifters. Base your warmup poundage on your contest reactions. You may find that a weight between the two extremes is your best bet.

Proper selection of poundages is one of the most important considerations in lifting competition. I have many times seen stronger lifters lose contests due to unwise selection of attempts. During a contest ignore all your competitors while you do your presses, snatches, and your first clean & jerk. If you are trailing after the press don’t get rattled and call for “all or nothing” attempts on the snatch. It’s a sorry lifter who finds he has nothing after realizing he could have had a fighting chance going into the clean & jerk had he only snatched what he had originally intended. Don’t let your competitors determine your first seven attempts. The last two clean & jerks are reserved for them.

There are times when you might decide to change your starting weights from your original goal. This can occur when you find the judging much stricter than you had anticipated. Or when the lifting conditions are poor – such as an unstable platform or a badly bent bar. This can be somewhat unnerving, especially after you have been concentrating on definite poundages. You must assume that this is not a disadvantage as far as the competition is concerned since your opponents will have to lift under the same handicaps. Also you will likely win with lighter weights than you had planned.

I have often been asked what I think about as I chalk up just before a lift during an important contest. The details of these little sessions were different each time, but the purpose was always the same. I would try to increase my desire to do the weight. This I would do by thinking of things like how important this lift was in the contest or the impression my success would make on my friends, teammates, coaches or myself. Then I would try to convince myself that I could do the weight. I would usually do this by recalling a previous successful lift with a heavy weight. Then just before making the attempt I would imagine myself succeeding with the weight. The temperament of the lifter determines how effective this type of preparation will be. The lifter who is greatly inspired by the crowd and competition benefits most. One who can only repeat in the contest what he has done in training won’t get too much out of this sort of thing. I firmly believe the lift is either made or lost before the bar is touched. You must approach the bar with a positive attitude, and how you do this should be based on your particular temperament.

After you have squeezed as much out of your presses and snatches as you can without regard to your competitors and gotten in your first clean & jerk the contest really begins. Now the tension grows as the crisis approaches – that awful moment when the entire championship hangs in the balance. No matter how long you have been lifting, if winning is important to you, you will experience some agony during these moments. When this feeling is no longer with you, it is time to start thinking of retirement. You will eye your competitor to see how he is taking the strain. It’s a little unnerving when you see him exuding an air of self-confidence. Don’t let this upset you. Those who give these airs are usually most disturbed, and they put on their act to keep it from showing. Remember if your opponent has a strong desire to win the pressure is just as rough on him as it is on you.

I used to have a reputation of being a worrier before a championship. My Egyptian foe, Kader el Touni, always strutted around with a cocky self-assurance. In 1951 in my dressing room as I was getting into my lifting outfit I was nervous and began to sing. I did this to keep my mind off the contest. But the impression I gave was that for the first time before a big match I was loaded with confidence. Touni, who up to this point was a picture of complete self-assurance, walked by my door and heard me. The effect nearly buckled his knees. He could no longer put on his act and on the platform he made poor attempts with weights he had done easily in training.

Remember the next time you see one of your opponents acting cocky to picture him as a little boy whistling in the dark.

While waiting for your opponent to attempt a weight don’t feel guilty about hoping he misses it – it’s only natural during the heat of competition and nearly everyone does. But for your own sake always consider that he will make it, and start thinking about the weight you will have to do after he does it. It is always easier to adjust your thinking downward than up.

Your reactions after the last lift is over to a large extent determine your future success or failure. Never apologize for winning. If you closest competitor missed all his snatches, accept your victory graciously. it does not matter that he dad none more in another contest. You are the champion because you had better control of the situation. Act like one, and consider this win another step toward your ultimate goal. Start thinking of the next title you will conquer. This does not mean you must act arrogant or become a braggart. At all times be a gentleman, but use this win to boost your mental attitude.

There is probably not a champion alive who takes a loss lightly. Losing is a bitter pill but when it is thrust upon you use it to your advantage. There are at least four ways to take a loss:

1.) you can laugh it off and forget it;

2.) you can make alibis;

3.) you can worry and become upset;

4.) you can plan your revenge.

Good sportsmanship is to be admired, but you entered the competition to win. If you ever expect to become a champion you will not take your losses lightly. Again this does not mean you should conduct yourself other than as a gentleman. Congratulate the winner regardless of how he won or why you lost. You will want him to do that for you after the next time you meet.

Don’t waste your time trying to dig up excuses and alibis. The better they are the tougher they make it for you to win the next time. Likewise do not permit yourself to become depressed – nothing can put a bigger damper on your total.

Losing stirs up the emotions os a champion or potential champion. These emotions should be directed to your benefit. Releasing them in one of the first three ways will do you no good and may harm you. The fourth way will let you come back a champion. When I say you should plan your revenge I don’t mean that you should maintain a grudge against the man who beat you. I do mean you should plan to beat him soundly next time you meet. Your only chance to get back at him is on the platform of the next contest. Start planning for it now while you can convert the emotions of losing into the enthusiasm for winning. Figure out a realistic plan on how you can do it. You have just received a wonderful opportunity to stage a comeback.